My Own Private Star Trek

by Jon Lomberg

Copyright ©2009 Jon Lomberg. All Rights Reserved.

I wasn’t a fan of the series when it first came out. The first episode I recall seeing was in the summer of 1967. It was the episode was about a Shakespearean actor in some murder mystery. I was staying with some hippie friends at a beach house on Long Island. I got bored after 10 minutes and returned to the beach to smoke a joint and admire the real stars.

2001: A Space Odyssey—now THAT was science fiction. Clarke’s cosmic view of human destiny captured what had always obsessed me about space exploration. The cheesy effects and cheesier writing of that episode of Star Trek did not whet my appetite for more.

Image: Artist Jon Lomberg with the black hole fountain he designed for the center of the Galaxy Garden.

A few years later, when I was beginning to show my art at SF conventions, I couldn’t help but absorb some of the excitement of fans, and eventually started watching the show in reruns. But it was a guilty pleasure. Reading the Shklovskii/Sagan’s book “Intelligent Life in the Universe” was much more congenial to my own developing visions of space. Carl himself was contemptuous of Star Trek. Bad stories and bad science did not represent the space program in the most positive light, nor did a galaxy filled with humanoids of roughly similar technological development follow his own sense of what Galactic Civilization might be like. He did like the diversity of the crew, which itself was a cultural breakthrough, even if the sexism had the women as little more than nurses, phone secretaries and coffee deliverers.

I met Gene Roddenberry in 1976, at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, on the night Viking 1 landed on the surface of Mars, about which I was making a documentary for CBC radio. Roddenberry and Nichelle Nichols were in attendance, along with Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury and other luminaries.

Not yet 30, I was brash enough to alienate Roddenberry with the following question/observation: most Star Trek fans of my acquaintance were less interested in missions to Mars than in trivia like the name of Kirk’s brother. Gene bristled and defended his fans as believers in the space program, and he and Nichelle did end up giving me some usable quotes.

(I do stand by my assertion 30+ years later, and it is born out by the recent movie, which is completely character driven and self-referential. The excellent casting found actors who plausibly play the crew in the film version of an Origin Issue in superhero comics. The film is really not about space at all —there’s no exploration, no interesting aliens, no sense of wonder. Fans who loved the characters will love seeing how everybody met. Fans of the slash fanzines [amateur stories of a sexual nature with all possible couplings, including gay Kirk/Spock storylines] will love seeing the heat between Uhura and Spock. But it’s really just soap opera with better effects).

Image: Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. Credit: Paramount Studios.

I was working on COSMOS at KCET in Hollywood when Star Trek:The Movie was in production. Those of us making the animations for COSMOS were worried that a big budget movie would make our sequences look awful by comparison. Then we started hearing horror stories about the sad fate of SFX creator Robert Abel, who lost his shirt and his company when the effects for ST:TM ran into trouble. There were lots of problems with that movie, including weak depictions of space itself, but the film’s most redeeming quality was its incorporation of the Voyager Record into the plot. It closed the circle of real and imagined space exploration in a way that I found very satisfying, having worked on the real Record myself.

When Star Trek:The Next Generation came out, it won my heart. Everything was better — the stories, the acting, the imaginary technology, even the uniforms. And space itself looked good — finally. A lot of the credit for that went to my COSMOS colleague Rick Sternbach, who along with Michael Okuda acted as art and technical advisors. Besides designing the look of all the technology, their role went something like this: a writer would call and say “We need something to go wrong with the engine.” Rick and Mike would come up with something like “tachyon pollution of the dilithium crystals.” The writer would respond “Great, now how do they fix it?” and Rick and Mike would describe how reversing the polarity of the anti-matter flow would solve the problem (reversing the polarity being the all-purpose sf equivalent of smacking the TV set on the side to eliminate the static).

In 1989, my wife and I were at JPL for the Voyager spacecraft’s encounter with Neptune. Rick invited us to visit the ST:TNG set, which was wonderfully memorable. We toured the bridge, sat in 10 Forward, and learned some backstage truths about, for example, how budget determined whether the Enterprise used warp drive or stayed at impulse power: impulse drive only required stagehands to slowly roll a painted starfield past the viewports; warp effects out the window required more expensive blue-screen compositing. If an episode was going over budget, they had to drop out of warp and make do with impulse.

Best of all, ST:TNG presented a positive view of the future. We have always been much better imagining hell than heaven — and readers of Dante’s Inferno must outnumber readers of his Paradiso by orders of magnitude. For the most part sf films deal with horrors of the future of the killer computer, homicidal robot, devilish alien, post-nuclear apocalypse variety. Exciting movies, but who would want to live in any of those futures?

But ST:TNG presented a future that was positive in every respect, with humans who had somehow surmounted all the problems that currently beset our world. Sagan finally came around to seeing the series as a positive contribution to public attitudes about space exploration, and Gene Roddenberry was an active supporter of the Planetary Society, the organization Carl founded to demonstrate public support for NASA science programs. (Majel Barrett Roddenberry later narrated a Planetary Society video in which these contrasting sf futures were compared).

The Star Trek franchise developed more TV and film projects and retained a strong bond with NASA, to the point where the prototype Space Shuttle was named Enterprise. The Star Trek universe became a common reference point for science fiction fans and space science buffs. Even the “science” of Star Trek could be used to sweeten the teaching of real physics.

In this sense, the new movie, enjoyable and nostalgic to old fans (but perhaps incomprehensible to newer ones) represents a backward step. I couldn’t recognize in the credits any names from the Paramount crew that had guided the development of all new additions to the Roddenberry canonic universe. Even the technology seemed all wrong. ST:TNG’s solid-state, no moving parts engine room, where never a grease spot appeared, was replaced with what seemed like a petrochemical facility, with miles of piping, valves, and lots of sloshing liquids labeled “reactant” (and shouldn’t that be “reagent”?) It just did not feel right, even allowing for the fact that it was a century earlier than Geordie LaForge’s spotless engine room.

Since this movie seems to have opened the possibility of subsequent adventures of Kirk’s crew, we can only hope that the films-to-come will return to the trajectory of boldly going someplace other than to a battle.

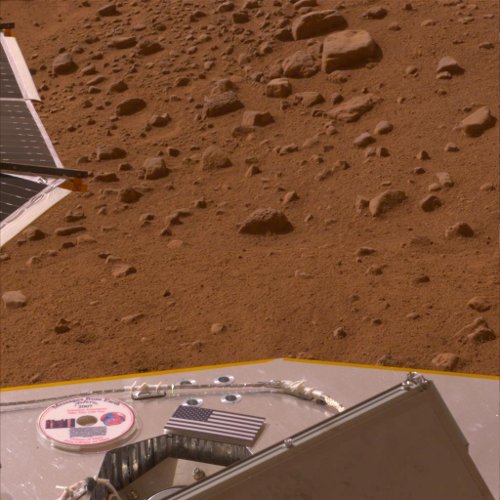

My own connection with the Star Trek universe is now on Mars, part of the Planetary Society’s Visions of Mars DVD carried aboard NASA’s Phoenix lander, presently somewhere in that cold desolation of sand, rock, and (yay!) ice. This disk is a gift to the future human inhabitants of Mars. It represents the important symbiosis between sf and real space science. It reminds those who live on Mars that it took the dreams of visionaries to have gotten there.

Image: The Mars DVD aboard Phoenix. The DVD is mounted on the deck of the lander, which sits about one meter above the Martian surface, visible in the background. Credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona.

As Director of this project, it seemed important to me that Star Trek be part of the package — and it is. There is an image of the (never seen in close-up) plaque on the bridge of ST:TNG’s Enterprise, giving the ship’s commissioning date and the fact that it was built in the Utopia Planitia shipyards on Mars (bet you didn’t know that). A section of the disk containing Orson Welles War of the Worlds radio broadcast is introduced by the voice of Patrick Stewart, the actor who played Captain Jean-Luc Picard. Also in that section is part of that radio documentary I did in 1976, including the voices of Gene and Nichelle. Gene said, “The real space program provides the science, we supply the dreams that keep people interested.”

Amen to that. Let’s hope future Star Trek vehicles return to that mission.

Return to Articles

All prices quoted in US dollars.

Copyright ©2010 Jon Lomberg. All Rights Reserved.